About the Project: Frequently Asked Questions

Table of Contents

What is Triage?

Updated: 14th April 2022 – PPI feedback suggested minor changes to language for readability

Triaging is where a clinician combines available information to make a decision about what to do next.

For example, a clinician presented with a referral will usually have information about:

- the patient’s medical history

- the current difficulty, problem or a description of unmet clinical need

- details of the patient’s current or previous treatments

A clinician then has to decide:

- how urgently the patient needs to be seen (for example, for assessment with a clinician)

- which group of clinicians, specialty or team would be best suited to help

What is Digital Triage?

Updated: 14th April 2022 – PPI feedback suggested minor changes to language for readability

“Every hour spent in thinking and talking about whom to treat, and how, and how long is being subtracted from the available pool of therapeutic time itself” - Paul E. Meehl (1954) Clinical versus Statistical Prediction

Digital triage is an attempt to leverage technology to assist clinicians in triage tasks with the aim to personalise, expedite and improve access to care. chronosig is designed to improve triage in secondary mental health services by leveraging contemporary machine learning (ML) technology on information contained in large, routinely-collected electronic health record (EHR) data.

Each patient’s historical electronic health record (EHR) data captures one or more instances (or episodes) of care under mental health services. A referral is almost always provided as documentation to help the clinician reviewing the case make an accurate and timely triage decision.

chronosig will use natural language processing (NLP) techniques to represent a patient’s longitudinal signature (or ‘fingerprint’) – capturing their history, signs/symptoms and presenting difficulties – and then learn associations between these signatures and triage decisions (captured as explicit structured data in patient’s EHR data). The aim is to deliver a triage clinical decision support tool (CDST) that takes as input a patient’s referral documentation, utilises existing medical notes (when available) and delivers a suggested triage outcome to assist MDTs.

Why is Triage Important?

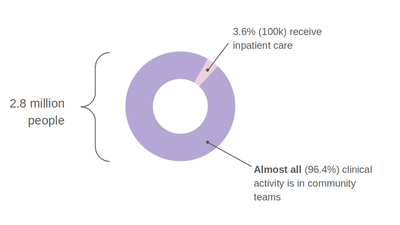

In the United Kingdom, mental healthcare is stratified into primary (led by General Practice), secondary (community and hospital NHS Trusts) and tertiary services (e.g. secure forensic services). In 2019-2020, over 2.8 million people in England were in contact with secondary mental health (SMH) services with the majority receiving care from community-based teams (NHS Digital, 2020).

Patients requiring secondary care are referred to a triage and assessment function, contained in community mental health teams (CMHTs) operating in NHS Trusts (collections of community-based clinics and inpatient hospitals). Referrals for triage and assessment are almost always via documents written by the referring professional who is most often a general practitioner (GP), a healthcare professional in an emergency department or member of a social care organisation.

In March 2021, across England’s mental healthcare NHS Trusts, there were 404,552 new referrals (NHS Digital, 2021).

Each referral requires the CMHT to:

instruct one of their clinicians to review the referral documentation alongside an examination of historical medical notes (e.g. if the patient is already known to SMH services)

use these findings for a discussion in a multi-disciplinary team (MDT) meeting

decide on an outcome for example:

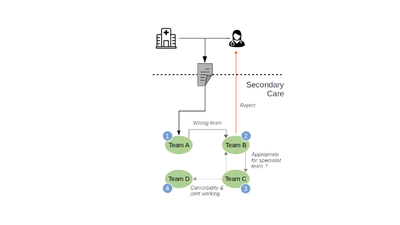

a. accept the referral and offer a first assessment appointment to the patient

b. reject the referral (e.g. if clinically inappropriate or the incorrect locality/service)

c. obtain further information (e.g. from the referrer, patient and carers)

d. refer to a specialty or locality team for further triage, assessment and treatment.

The cost of initial assessments arising from new referrals to SMH services was £326 million in 2018-2019 (NHS England, 2020).

Referral and triage processes lack transparency (to patients and referrers), are capricious (with CMHTs using referral criteria and thresholds inconsistently) and result in frustration from ‘referral bouncing’ (Chew-Graham et al., 2007).

Patient care is delayed because they are being triaged multiple times, by different teams, who may disagree on the most appropriate treatment team for the patient’s needs.

The delay in accessing treatment (after referral) has been labelled the hidden waiting list by The Royal College of Psychiatrists who identified that two-fifths of patients end up accessing emergency or crisis care (RCPsych, 2020).

Displacing patients with unmet mental health needs impacts on other NHS services – for example, in 2013-2014, there were 6.2 million emergency department attendances across England for mental health needs with around half being discharged back to community care (Baracaia et al., 2020).

The referral and triage process is one target for process improvement where both patients and clinicians stand to benefit.

To this end, the chronosig project directly addresses the strategic priorities described in the Topol review (Foley & Woollard, 2019) and the NHS Long Term Plan (NHS England, 2019) that emphasise the use of EHRs to improve and personalise care for individuals.

How chronosig Works

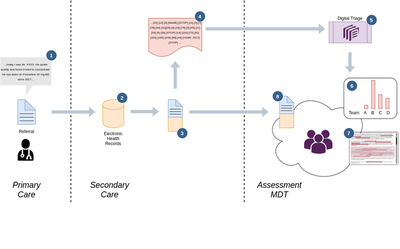

The diagram above outlines how chronosig works for digital triaging:

- A patient visits their GP (in primary care) for a mental health problem. Their GP makes a referral (e.g. by email or letter) to the nearest secondary mental health NHS trust.

- The referral is securely stored in the secondary care NHS Trust’s electronic health record (EHR) system

- Sometimes, the same person will have historical records (clinical notes) from previous contact with mental health services – when available, this data is appended into one large patient document that captures the current issue as well as a near-complete record of the patient’s history

- The patient document is then converted into a machine-readable format – this is where text and words are converted to numerical representations; for example, the word “MOOD” will be converted to a unique number such as

2048, “INSOMNIA” to184, “LOW” to276and the word “WITH” to the number4. So if the patient document contains the sentence “low mood with insomnia”, the resulting numerical version would be{276, 2048, 4, 184}The result is a very large sequence of numerical data (called a tokenized string) which represents the complete patient document.

Referrals to secondary mental healthcare are triaged by a multi-disciplinary team (MDT) in “assessment meetings” where a group of mental health professionals will review each referral and decide on the most appropriate team for a given person.

- chronosig takes a tokenized version of the patient document as an input. chronosig has previously been trained) on tens-of-thousands of anonymised patient documents to a) locate and identify common patterns in the tokenized streams and b) to match these common patterns to treatment teams within secondary care. chronosig can then recommend which treatment teams have previously accepted and treated similar patients.

- chronosig’s recommendation is delivered to the MDT, which in the example above, shows that Team B is the best matching team, followed by Team C, D and then A.

- To help clinicians use chronosig’s recommendations robustly, the original patient document is displayed with highlighted regions showing the patterns in that chronosig used to make it’s recommendations – this helps ensure that clinicians are aware of what features of a given patient are relevant to the recommendations chronosig makes

- There will be situations where chronosig’s recommendations are inconclusive or don’t make sense to the clinicians in the MDT – in these circumstances, the MDT will review the full patient document to complete the triage process

Who Supports chronosig?

The project is funded by the National Institute of Health Research (Grant Number: AI_AWARD02183) and hosted by the Department of Psychiatry at the University of Oxford, Oxford Health NHS Foundation Trust and the Oxford Health NIHR BRC.

Data, Privacy and Security

Updated on 21st February 2022: the UK-CRIS network has been renamed the Akrivia Health Network

Updated on 8th March 2022: additional links to the Akrivia Health Network website on data use-cases added

chronosig makes use of medical data, specifically, that contained in the electronic health record (EHR) of specialist, secondary mental health NHS trusts. The data required to build the chronosig clinical decision support tool (CDST) for triage will be obtained from the Akrivia Health Network (AHN), formerly, the UK-CRIS network. UK-CRIS network was a collaboration between sixteen secondary mental health NHS trusts across England participating and contributing electronic health record data to a secure research environment. The relationship between UK-CRIS and the new AHN is described below.

All data in the AHN is anonymised and access is strictly controlled to authorised and qualified researchers (described in the subsections below).

Neither chronosig (or the UK-CRIS network more generally) link data from secondary mental health care EHRs to any other healthcare records (for example, data is not linked to GP or other local hospital records). All data used in the chronosig project is historical data – no patients actively being treated or triaged are used.

Akrivia Health have their own webpage here which also describes how they process, store, anonymise and make data available as well as a description of the intended uses.

In the following sections, we have describe details of how chronosig uses data and how the project specifically relates to the Akrivia Health Network and Platform.

We welcome any questions (or suggestions on how to make this material more useful) and you can contact us by the webform or email addresses here)

Who processes and maintains the Akrivia Health Network (UK-CRIS) database?

Storing, anonymising and making data available to researchers in a secure environment requires significant expertise and computing resources. For this reason, Akrivia Health was founded in May 2019 to run, sustain and grow the original UK-CRIS project. Akrivia Health is a University of Oxford commercial spin-out company, partly owned by the NHS and formed to continue and sustain the original UK-CRIS consortium which was funded by the National Institute of Health Research (NIHR) and was based at the University of Oxford and the NIHR Oxford Health BRC.

Where is Akrivia Health Network data stored?

Akrivia Health manage and administer the secure storage of the AHN database on a cloud-based platform (Amazon Web Services, or AWS). The use of AWS cloud storage follows the UK government’s policy from 2013 to migrate public-sector data to secure cloud systems to minimise the use of “physical” storage located at and managed individually by each organisation (where there are overhead costs and very often, less expertise and resource for providing reliable, continuous 24/7 services). Cloud storage is preferred over traditional “in house” physical storage and backup because it is fault-tolerant – if a traditional server fails, everyone dependent on the data loses access until a backup can be restored. With cloud-based storage, data is distributed over many physical storage devices and access can be restored almost seamlessly in the event of failure. AWS (alongside Microsoft Azure and Google Cloud) are already used by the NHS and the public sector more generally to warehouse mission-critical data to prevent loss-of-service and ensure data integrity.

What Data is Available in Akrivia Health Network data?

NHS trusts regularly upload extracts of their clinical electronic health records to the AHN using Akrivia Health’s AWS-based platform.

These extracts contain pseudonymised and “masked” versions of:

- Clinical notes, letters and correspondence, refered to as ‘unstructured’ free-text. This data provides descriptions of patient’s health state including symptoms and signs, descriptions of clinical or treatment decisions/reasoning and treatment plans including psycho-social interventions as well as medications.

- Structured data such as demographics e.g., dates of birth, categorical gender data and diagnoses.

How is confidentialty ensured?

As part of Akrivia Health’s data processing activities, on behalf of NHS Trusts in the AHN, Akrivia Health provides services to ‘deidentify’ (i.e. remove personally identifiable information) all data contained in the database. Importantly, all data placed in the AHN database is pseudonymised by masking – this is where any patient-identifiable “fields” or data points (including names, date of birth, address, NHS number) in a patient’s electronic health record notes are ‘blanked out’. Pseudonymised records for a given patient can be linked back to the identity of a person (e.g. their NHS Number), but Akrivia Health are not permitted to do this – only the NHS Trust to which a patient is registered can re-identify AHN data and only for specific applications, such as locating a Trust’s local patients who might be eligible for specifc research projects. These reidentification processes are separately governed by research ethics and oversight processes at the local NHS Trusts.

Specifically, for chronosig, there is no need to re-identify any patients and only pseudonymised, masked data will be used.

How does ‘Masking’ Work?

In unstructured, free-text we might find descriptions such as:

“Mr Jones is a 67-year-old man (DoB: 24/1/1954; NHS Number 1234 345 123) who is currently living at 42 Some Street, Somewhere, SO14 0NB with his 4 children.”

This data will be stored in the AHN database as:

“Mr XXXXX is a 67-year-old man (DoB: XXXXX; XXXXX XXXXX) who is currently living at XXXXX, XXXXX, XXXXX with his 4 children.”.

This masking is performed automatically when data is uploaded to the AHN platform from each NHS Trust. Further, structured data (i.e. data not written by clinicians in a ‘narrative’ free-text format, such as demographic data that is usually captured by standardised electronic forms) is masked in the same way.

The same underlying data on AHN is also further aggregated into anonymised high-level summary data that can never be re-identified – this means reducing the level of detail in the dataset for example, only showing the year in which a subset of patients were born or truncating post-codes to describe only medium- or large geographical regions. This summary-level anonymised data is accessible to authorised AHN users and Akrivia Health staff and can be used to answer high-level questions; for example, to profile the dataset with queries such as “How many people aged between 18 and 65 have a diagnosis of depression and are taking one of the common medications used to treat depression”. These kinds of high-level data queries do not use or reveal the underlying masked, free-text or structured data.

How does the Akrivia Health Network Prevent Accidental or Deliberate Re-identification?

One overarching confidentiality principle is that data that could identify any individual patient (e.g. name, address) should never be disclosed to any user of AHN database and the methods described above ensure this by directly masking patient-identifying data items or fields. Further, given any amount of such anonymised data, the actual identity of an individual should never be able to be recovered indirectly, either accidentally or deliberately.

This is a particular risk when two distinct and anonymised sources of data are combined or linked. For example, assume that in the AHN database there is only one male patient, aged 53, diagnosed with depression living in a particular geographical region (e.g. a top-level postcode such as OX1). If this information was combined with, for example, a DVLA database of drivers living at specific streets in OX1 and there was only one male 53 year old driver in that database, one could infer that the 53 year old male patient with depression is the same person who lives at the address contained in the DVLA database.

For this reason, Akrivia Health Network (AHN) data are never linked to other NHS, public sector or commercial datasets without explicit research ethics committee approval – i.e. above and beyond those processes for the usual approval of AHN projects – in those cases, explicit contingencies have to be put in place to mitigate such identification risks and this usually involves stating that if, on combining the two databases, there are less than a threshold number of patients (for example, 10) then those patients will not be used analysed or reported in the combined, linked data set.

For the chronosig project, there will be no data linkage with other NHS, public sector or commercial databases.

Can people opt-out of the Akrivia Health Network database?

Yes – this can be achieved by contacting your local NHS secondary mental health care trust, or via the National Data Opt Out scheme.

When patients opt-out, their electronic health record is “flagged” so that their NHS Trust ensures opted-out patient data is never extracted and placed in the AHN database.

Where can I find out more about the Akrivia Health Network and Privacy?

Oxford Health NHS Foundation Trust has a helpful guide that elaborates on these issues further here. Note, this web-site still uses the term ‘CRIS network’ which is now synonymous with the AHN (Akrivia Health Network).

Who can access Akrivia Health Network data?

Collections of patient records in the masked format described above are made available to researchers who are suitably qualified (meaning that all users must be vetted by their local NHS Trust’s information governance teams) and are

- NHS employees who do research

- researchers employed at the University attached to an NHS trust who have been through the Trust’s vetting process

In addition, data in the AHN pertaining to patients belonging to a given NHS Trust are only accessible to staff who are employed by that Trust or the associated University; for example, researchers at the University of Oxford and Oxford Health NHS Foundation Trust are not allowed to access data on patients from other external trusts in the AHN without formally applying to that external trust and meeting that trust’s information governance and oversight requirements. Similarly, Akrivia Health staff cannot routinely access these data without express permission from the NHS trust that donated the data and then, only for a specific task/research project for a specified period of time.

When making an application to use data for any given research project, the researchers must make a clear case for why using AHN data is necessary and demonstrate how the proposed research use of the data is proportionate and obeys the seven principles of the UK’s General Data Protection Regulations (GDPR)

Specifically for chronosig we are making individual applications for specific subsets of the Oxford Health NHS Foundation Trust AHN data to Oxford Health’s Oversight Committee.

Similarly, we will be repeating that same process at each partner NHS Trust (listed here) – only if these NHS Trust’s are satisfied that chronosig is proposing an appropriate and proportionate use of data will they make subsets of their data available to the project via AHN and the AWS platform.

How do authorised users access the Akrivia Health Network database?

To access any subset of the AHN database, appropriately qualified and authorised users must use a secure AWS workspace – this refers to the cloud-based storage system, at Amazon Web Services, used to warehouse the AHN data.

Authorised users are required to log onto AWS using a secure connection (much like the Virtual Private Networks (VPNs) that are available for private internet browsing on any computer) and the user is presented with a desktop (i.e. the same way one would be if logging onto their own physical Windows, Linux or Mac computer) called a “virtual desktop”.

On this virtual desktop, the user accesses only the subset of AHN data they have been given express permission to use (as described above). Users can then start analysing the data in that same virtual desktop. The virtual desktop has no internet access (i.e. users cannot launch a web browser inside the virtual desktop) and users cannot copy and paste data from the virtual desktop onto the physical computer they are using to access the AWS workspace.

If users wish to export any files from this workspace to their local computers (for example, if a researcher wants a summary table of results from an analysis to put in a research report or publication), this must be manually inspected and approved by each Trust’s oversight team. Any approved export actions are also automatically logged for audit purposes. If there is any doubt about e.g. inappropriate use or a risk that confidentiality would be breached, the request to export summary data will be denied.

In summary, when authorised researchers are using the AWS Workspaces virtual desktop to view, analyse or manipulate data in the AHN database, they are effectively “sealed off” from the internet and their ‘physical’ computer. A researcher can view and interact with only the specific subset of AHN data that they have been approved to access/analyse and data cannot be moved from the virtual desktop to any other computer (including the physical computer the researcher is using to access the AWS workspace).

Specifically for chronosig, all access and analyses (including development of the digital triage tool) of pseudonymised patient level data in the AHN database will be conducted inside the AHN platform via a unique AWS Workspace assigned to each individual researcher.

What mechanisms protect access to Akrivia Health Network data and Virtual Desktop/Workspaces?

When logging onto the AHN network via AWS workspaces, the user must provide all of the following:

- a username (granted by the researcher’s home NHS Trust)

- a strong password or passphrase

- a temporary pass code generated “on the fly” by an authenticator application – so-called two-factor authentication.

Usernames and passwords are ‘static’ – once set, they only change periodically (e.g. monthly) and are stored (in an encrypted form) so that a user’s credentials can be verified on logging on to any password-protected system.

For this reason, although generally secure, passwords can be ‘cracked’ by determined unauthorised users (hackers). To mitigate this, almost all security-critical applications now insist that a second line of authentication is used. So called two-factor authentication (2FA) is where (as well as the username and password), a registered user must register a physical device (usually, a smart-phone) to generate “instant” passcodes (usually, 6-digit numbers) that change every 30 seconds. This is the same approach that retail banks use for customers accessing their accounts online. After entering their username and password, the AWS platform then requests the user enter a 6-digit code by opening an authentication app on their registered mobile device. If the username, password and the 2FA 6-digit passcode are all correct (in the 30-second window) only then is the user authenticated and logged onto the system. In practice, this means if anyone ‘cracks’ a username and password, they still cannot access the user’s account on the AWS workspace and consequently, the Akrivia Health Network platform because they need to physically possess the authorised user’s mobile phone to obtain a 6-digit 2FA passcode.

References

Chew-Graham, C., Slade, M., Montana, C., Stewart, M., & Gask, L. (2007). A qualitative study of referral to community mental health teams in the UK: Exploring the rhetoric and the reality. BMC Health Services Research, 7(1), 117. https://doi.org/10.1186/1472-6963-7-117

Foley, J., & Woollard, J. (2019). Digital Future of Mental Healthcare Report. https://topol.hee.nhs.uk/wp-content/uploads/HEE-Topol-Review-Mental-health-paper.pdf

NHS Digital. (2020). Mental Health Bulletin: 2019-20 Annual Report. https://digital.nhs.uk/data-and-information/publications/statistical/mental-health-bulletin/2019-20-annual-report

NHS Digital. (2021). Mental Health Services Monthly Statistics, March/April 2021. https://digital.nhs.uk/data-and-information/publications/statistical/mental-health-services-monthly-statistics/final-march-2021

NHS England. (2019). The NHS Long Term Plan.

NHS England. (2020). National Cost Collection 2019. NHS England and NHS Improvement. https://www.england.nhs.uk/wp-content/uploads/2020/08/1_-_NCC_Report_FINAL_002.pdf

RCPsych. (2020, October 6). Two-fifths of patients waiting for mental health treatment forced to resort to emergency or crisis services. Www.Rcpsych.Ac.Uk. https://www.rcpsych.ac.uk/news-and-features/latest-news/detail/2020/10/06/two-fifths-of-patients-waiting-for-mental-health-treatment-forced-to-resort-to-emergency-or-crisis-services